2026-02-09

When you stand in a field or in front of a farm supply store, faced with a dazzling array of fertilizer packaging – organic fertilizers, compound fertilizers, and biofertilizers – have you ever wondered: what are the differences between them? Which one should I choose? The best way to answer this question is to "trace the origins," understanding their distinctly different "birth" processes. From raw materials to processes and ultimately to their effects, these three are like the "three pillars" of the agricultural nutrient world, each undertaking a unique and important mission.

I. Raw Materials and Costs: The Difference Between "Waste Products" and "Industrial Products"

Fertilizer production begins with raw materials, and the differences in raw materials directly determine the cost structure and product properties.

The main raw materials for organic fertilizers are organic waste such as livestock and poultry manure, crop straw, and food processing residues. This "turning waste into treasure" model makes the cost of obtaining raw materials relatively low, but the collection, transportation, and pretreatment processes require a certain investment. Therefore, its value is more reflected in environmental protection and resource recycling.

The raw materials for compound fertilizers are chemical products such as urea, monoammonium phosphate, and potassium chloride. Their costs are closely linked to international commodity prices and are subject to significant fluctuations. Behind the high raw material costs lies their core value of providing precise, high-concentration nutrients.

The raw materials for biofertilizers are the most unique; the core is specific functional microbial strains (such as nitrogen-fixing bacteria, phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria, etc.) that have been screened and cultured, supplemented with peat, composted organic fertilizer, etc., as carriers. The core cost lies in the research, cultivation, and preservation technology of the microbial strains, making it the most technologically advanced.

II. Core Process: A Dialogue Between "Microbial Decomposition" and "Chemical Synthesis"

The production process is the most crucial criterion for distinguishing the three types of fertilizers, and their complexity varies greatly.

The core of organic fertilizer production is aerobic fermentation and composting. This is like a "slow cooking" process dominated by microorganisms. The raw materials are regularly turned in fermentation tanks or piles using turning machines to create the best environment for aerobic microorganisms. Microorganisms multiply rapidly, decomposing organic matter and releasing heat, causing the compost pile temperature to rise to over 60-70℃. This process effectively kills pathogens and weed seeds, converting unstable organic matter into stable humus. The entire process is lengthy, but the technical principles are closer to nature.

Compound fertilizer processing technology, on the other hand, is a highly industrialized "precision synthesis" assembly line. Its core process involves synthesizing nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium elements into uniform granules under high temperature or chemical action, using methods such as high-tower melting granulation or rotary drum steam granulation. This process is complex and energy-intensive, but it ensures that the nutrient ratio of each fertilizer granule is precisely consistent, enabling large-scale and efficient production.

The production of bio-fertilizers is like operating in a sophisticated "microbial factory." The core process involves the stepwise amplification of functional microbial strains, which are then adsorbed onto sterilized organic carriers. The entire process requires extremely high sterility to ensure the dominance and activity of the target microbial species in the product. The technical challenge lies in maintaining the high vitality of these delicate microorganisms during production and storage.

III. Applicable Scenarios: Soil's "Conditioner," "Nutritionist," and "Health Doctor"

Understanding their "origins" and "manufacturing processes" makes it easy to understand their respective optimal applications.

Organic fertilizer is the soil's "long-term conditioner." Through its rich organic matter, it improves soil aggregate structure, enhances water and nutrient retention capacity, and slowly releases various macro and micronutrients. It is best suited for improving compacted and infertile soils, serving as a base fertilizer to lay a solid foundation for crop growth, but its nutrient content is relatively low, and its release is slow.

Compound fertilizer is the crop's "efficient nutritionist." It can quickly and precisely meet the large demand for nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium during the vigorous growth period of crops, resulting in immediate yield increases. Therefore, it is widely used in topdressing for field crops and high-yield management of cash crops, and is crucial for ensuring food security.

Bio-fertilizer plays the role of a "soil ecological health doctor." It does not directly provide large amounts of nutrients, but through the activity of its beneficial microorganisms, it plays a significant role in nitrogen fixation, phosphorus and potassium solubilization, inhibition of soil-borne diseases, and stimulation of crop growth. It is often used in combination with organic fertilizers or compound fertilizers to improve fertilizer utilization and address specific soil problems.

Simply put, organic fertilizers focus on "improving soil," compound fertilizers focus on "increasing yield," and bio-fertilizers focus on "regulation." They are not mutually exclusive but complementary.

For growers, the most scientific strategy is "organic fertilizer as a base, compound fertilizer for a boost, and bio-fertilizer for enhanced efficiency." For example, apply sufficient well-rotted organic fertilizer before sowing to nourish the soil; during the critical growth period of the crop, apply compound fertilizer according to the nutrient requirements to meet peak demand; and for fields with continuous cropping problems or poor soil activity, appropriate bio-fertilizers can be used to improve the micro-ecosystem.

Choosing fertilizers is essentially choosing a way to communicate with the land and crops. Understanding the production logic and core value behind these three mainstream fertilizers will help you make wiser and more efficient choices, turning every investment into a more abundant return.

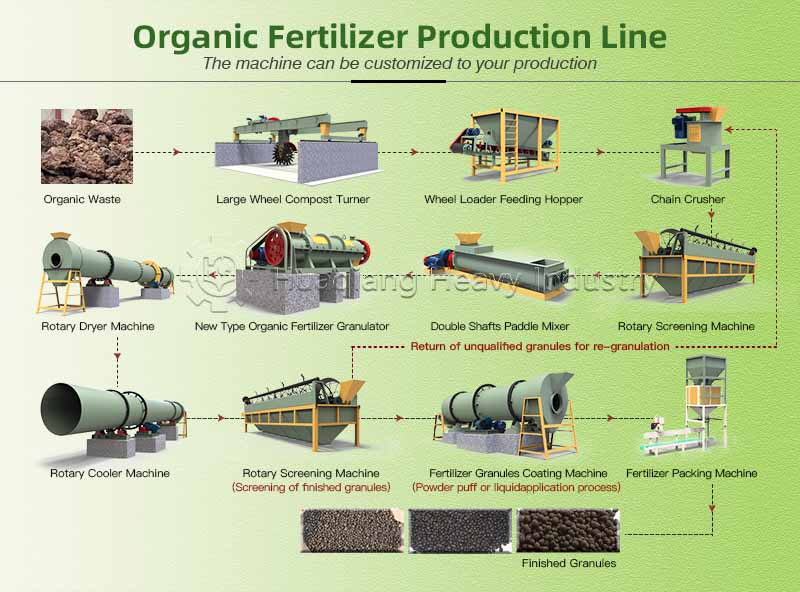

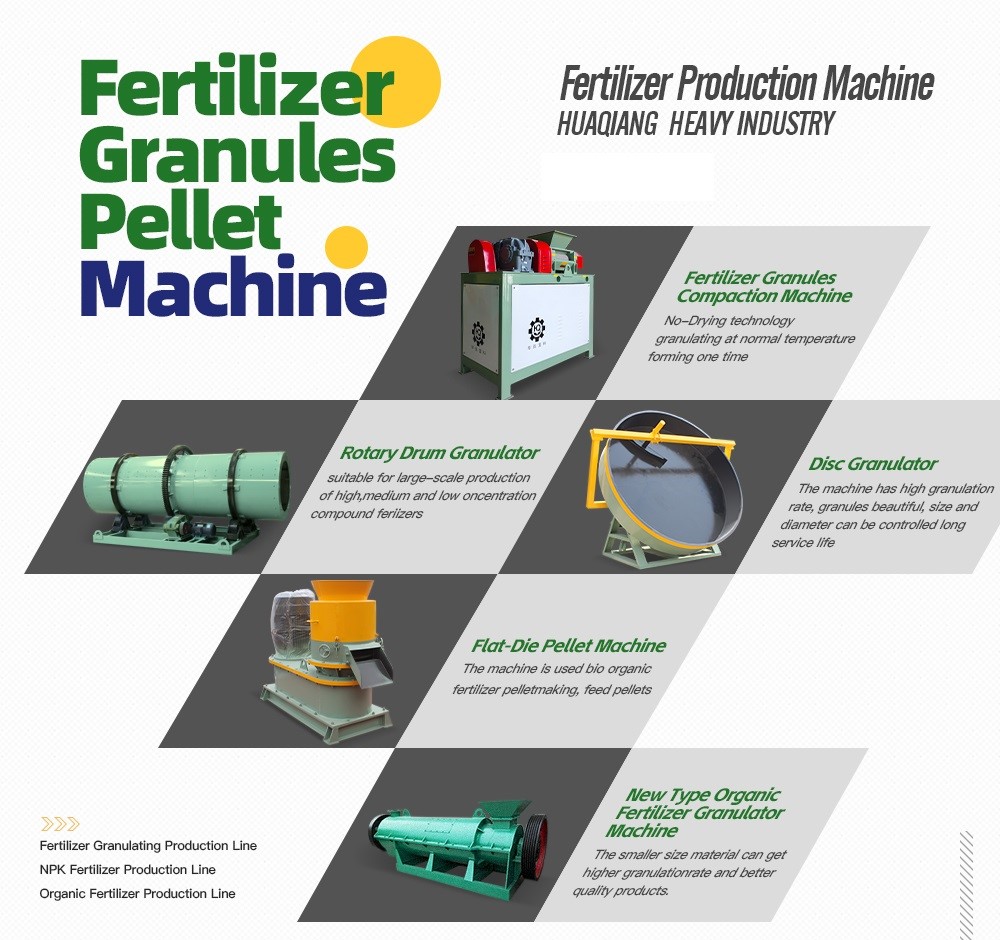

These distinct production logics are realized through specialized industrial equipment and fertilizer production machine technology. The npk fertilizer manufacturing process often utilizes a rotary drum granulator for agglomeration or a roller press granulator production line for dry fertilizer compaction. This line uses a fertilizer compactor to achieve fertilizer granules compaction without heat. In contrast, a bio organic fertilizer production line begins with the organic fertilizer fermentation process, efficiently managed by equipment like a windrow composting machine. Following fermentation, the material is shaped using granulation equipment similar to that used in NPK lines. The complete suite of equipments required for biofertilizer production thus integrates biological processing with physical granulation, enabling the efficient manufacture of these three complementary fertilizer types.